The Thing You Want Most Needs to Become the Thing You Take Least Seriously

How a low-stakes writing experiment unlocked 20 years of creative paralysis

24 years ago my life changed

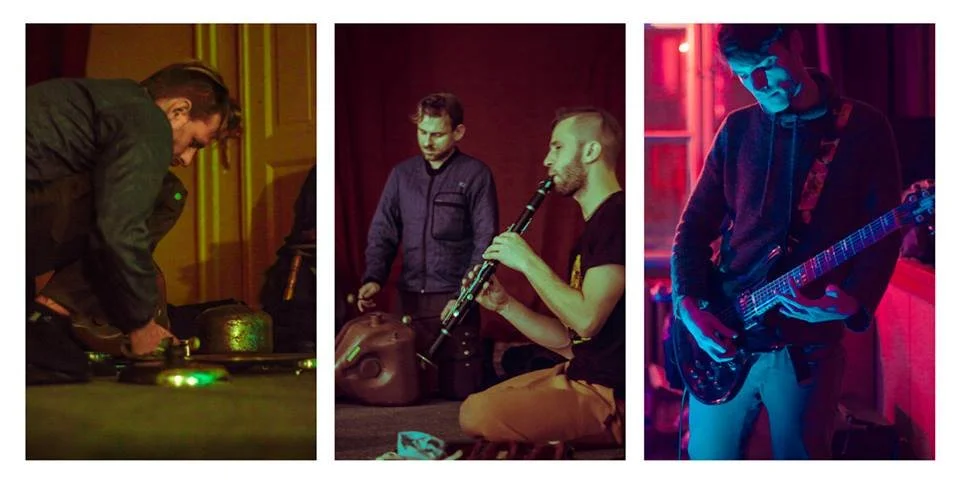

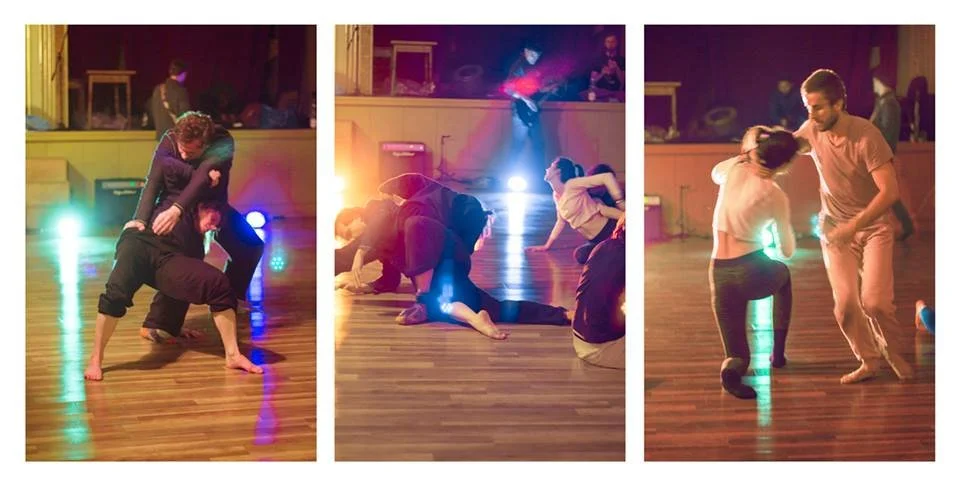

Jamming at Kinestrefa’s improv dance session (photo by Kinestrefa, 2015)

24 years ago, my life changed when my dad handed me a CD saying: “If even Jimi Hendrix is not doing it for you, try this”. The disk was titled The Best of Black Sabbath. That’s how I got hooked on music. My dad made me into a metalhead.

A year later, at 17, I decided to learn to play, and the electric guitar was the obvious choice with a bold dream of recording an album right from the start.

Fast forward to 2025, and I still haven’t written and published a song. Was it imposter syndrome or perfectionism that stopped me? Maybe I lacked talent or the guts to go after it? Maybe music was never meant for me? Maybe it’s time to get serious and forget those teenage dreams?

Those were the kind of questions I had been continuously asking myself until recently, when right here I started writing in public.

It still really puzzles me that 3 years of a very modest commitment to writing were enough to actually get started and publish weekly (well, last week was a bit of a hiccup due to holidays).

This experiment made me think that perhaps I can reverse engineer the process and teach myself to make music the same way I taught myself how to write.

What Actually Stopped Me

I’m writing this as a 40-year-old man, so it isn’t quite fair to be picking on me, the teenager from the past, but over the years, I became quite aware of what’s been holding me back from actually committing to what I always believed was my greatest passion of all time. Keeping music frozen for two decades.

Jamming with Paweł in a bunker (photo by TomaSz, 2009)

1. Refusing to Be a Beginner

From day one, I wanted to be a virtuoso, avant-garde, groundbreaking artist—looking up to my heroes at the peak of their artistic careers, while lacking realistic references or role models (that is, peers of my age into the same thing).

Quite ironically, the track that really fired up my desire to play was called Man Made God (by Swedish band In Flames) — a fairly good reflection of my grandiose ambition masking the insecurity of a young person growing up.

Much of it was rooted in my assumption that if I was already revealing some talent in drawing at that point, I was assuming anything else I touch needs to match that level. My favorite band in those days was Opeth, known for complex compositions, blending musical styles, and very, very long songs. That was the music I wanted to make and nothing less, right from the start.

I refused to accept and enjoy the humble early steps, and above all, I was pushing for the immediate results that I could use to prove myself to others, what people call these days, seeking external validation.

Lesson learned: be honest with yourself about where you’re standing, being a beginner is a beautiful place to be in many ways, that’s where you’re making the fastest progress (correct, going from zero to anything above is a monumental progress compared to going from good to great), do it for the fun of it, you don’t need to prove yourself to anyone.

2. Chasing Someone Else’s Dream

Growing up, I had to be resourceful, independent, and practical. Family of 5, not too much money, busy parents. If I wanted to get something done, I had to do it myself. If I wanted to learn something new, I had to figure it out by myself. Useful traits to develop early on, but also a big hurdle when it comes to doing things with others.

Being self-taught in pretty much anything I really care about made me also fairly arrogant and closed-minded because I only knew one way of doing things. Tendency to force my own ideas, not being open to listening, being dead set on a specific vision, and lacking flexibility were the trade-offs.

In those early days, I had the mentality of a one-man band dictator. It was what allowed me to build musical instruments with very simple means, but at the same time made me a bad collaborator.

In those early days, I was fascinated by stories of bands of friends who would spend their entire lives touring around the world together, making music. In many ways, that was the dream I wanted above the music-making itself.

Later on, in 2008, when I was an exchange student in Milan, I was a strange case of an “Erasmus” who, instead of partying, would spend the evenings in rehearsal rooms with other misfits hoping to join a band. When I finally found two guys who were relaxed about my inexperience, the year came to an end, and it was time for me to go back to Poland to finish my degree.

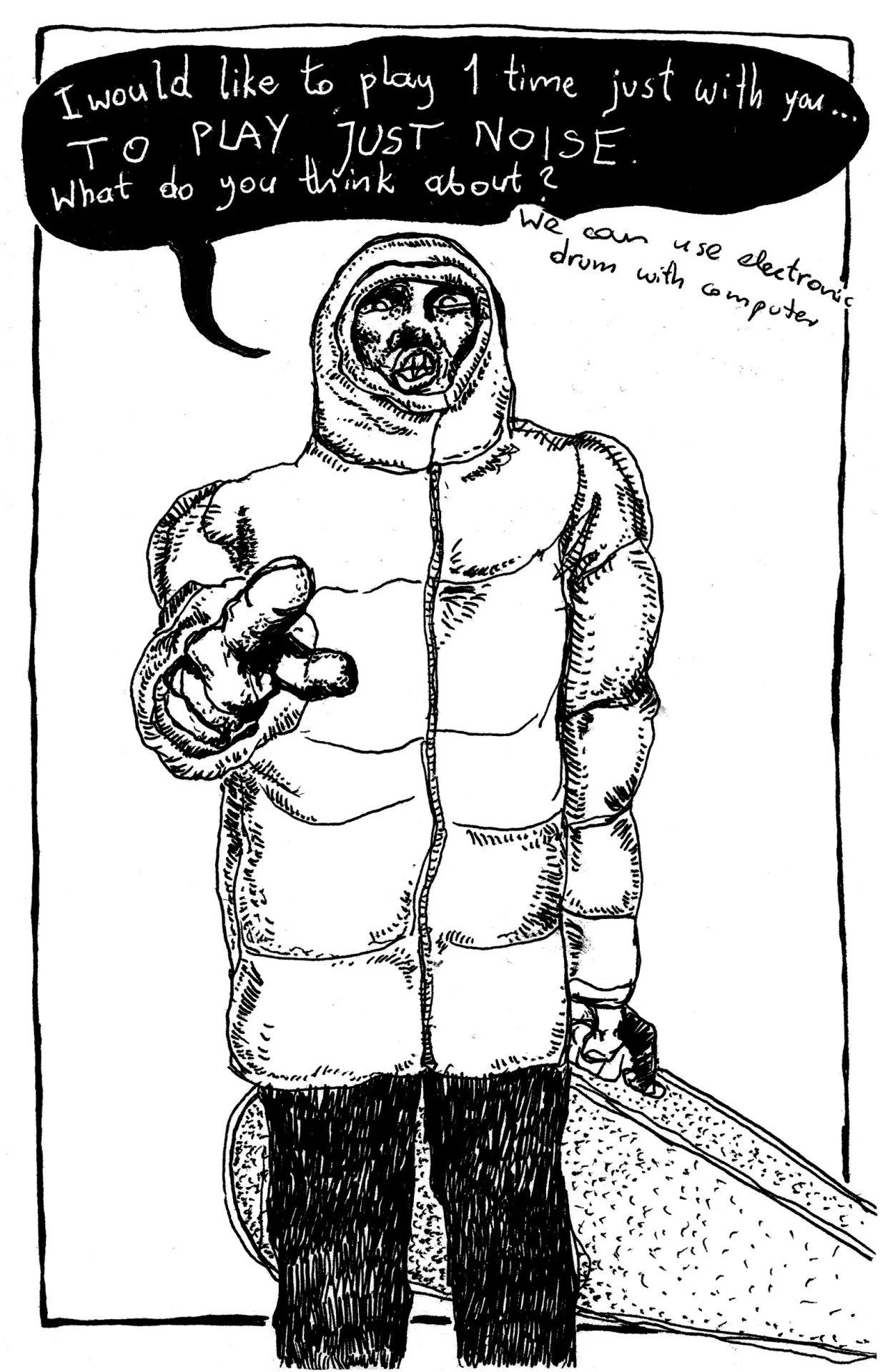

Met a whole lot of real characters in Milan (doodle by me, 2008)

I didn’t know really how to communicate musically in the first place, and I wasn’t quite clear with myself about what I wanted. In many ways, from the point of today, I was just looking for friends with an interest in similar music to go on adventures with. Music was at that point the background to those adventures.

I found in those days that building instruments was a better outlet for my creativity, where, just like earlier through painting, I was expressing myself and myself only at the level I was finding deep satisfaction in, while finding friends among people with whom I would connect on a different plane, without the prerequisite of having the same musical taste.

Lesson learned:

understand what it is that matters to you, and have a unique experience rather than trying to replicate someone else’s life. A single activity may be too little to fulfil all of your needs in life. Allow your life to be the main container that blends it all together.

3. Thinking My Way Through Instead of Playing My Way Through

I have always seen myself as a smart guy, and perhaps for that reason, I believed for most of my life that I could think my way through any problem. That it’s all about the understanding of things.

As an adult, I can surely state that it’s all about the capacity to experience things. And that requires experimentation, trying different things out. Iterating. I was doing the same thing over and over back then.

In my case, this is displayed in the belief that I have to master the guitar first before I can make a song. Other than the mastery is a vague territory, you can make a song with whatever skill level you’ve got. But you have to go for the thing.

Lesson learned: it’s the movement, your negotiating your relationship with the world and people around you, that leads to novel discoveries and growth. In other words, don’t overthink it. Just act on your interest and see where it leads you because you want to experience what you could never predict.

Earlier this year, a new guitar build project nearly hijacked my desire to play.

4. Hiding Until It Was “Good Enough”

My boldest step towards performing music was in 2015 when I was living in my hometown, Poznan, again. Taking part in live jams organised by my friends from Kinestrefa—a duo of dancers, Krystyna Lama Szydłowska and Zofia Tomczyk, would regularly curate a space for dance improvisation evenings with live music (also improvised). Anyone could join the dance floor, and anyone could bring their instrument.

My first-ever live jam experience with Kinestrefa (2015)

I have, at that point, opened up to a wider range of music, and because I always loved how the electric guitar can be manipulated with fuzzboxes and effects, I attempted the soundscaping approach to making music that felt more relaxed and forgiving.

I recorded those sessions, which objectively were very meaningful to me, even if my part was just buzzing in the background. I never published them, though. I just felt they weren’t showcasing my craftsmanship the way they should.

It’s quite remarkable that at the same time, both Krystyna and Zofia (who didn’t have my 13 years of involvement with music) created records with their friends.

I made a music video for one of the Lama’s songs, and Zofia keeps releasing her ambient tracks via Ciche Nagrania.

Lesson learned: it’s great to be ambitious, but don’t let it hinder your creative growth, undermining the work you’re currently producing—it is a testimony of just the current moment, keep making, and the work will eventually reach the level you want it at, and possibly some place you couldn’t even imagine.

A still from Lam Fatal’s music video (2019)

What about writing?

At this point, you may ask what it has to do with writing?

First of all, I believe that the meta skill (meaning an overarching superskill) of learning and making is transferable between domains. I proved it to myself many times. The only thing you really need to bring to the table is the willingness to do it and openness to accept that it will take the exact amount of time it needs to take (which you never quite know what it is, but once you commit to it, less than you thought).

My three-year writing evolution:

Weeks 1–3: The first few weeks felt like being back in school—awful, like I had homework to deal with. I was annoyed and felt dumb because I could barely fill a page with anything, not even something meaningful. Just getting the first words out caused friction. But I kept showing up.

Month 1–12: Around the one-month mark, I started noticing the first benefits, like mental clarity, and the satisfaction from feeling it becoming easier motivated me to lean into it. I actually started enjoying the process and stopped resisting it.

Year 2: The second year became all about discovering how I could enter flow in a predictable manner. Writing became a creative exploration rather than just documenting my life and venting—it was about amusing myself with what treasures were waiting in the depths of my mind. At the same time, I started raving about the benefits of writing to others rather than letting my writing speak for itself.

Year 3: Since April 2024, I moved to writing digitally, which, for the first time, allowed me to easily review my past entries (I can’t deal with my handwriting, so anything I couldn’t remember was essentially gone). By this time, it was already clear I wanted to start publishing eventually, but there seemed to be too much all at once—I didn’t know where to start. I spent most of August stuck overthinking and trying to create a manifesto, until the breakthrough happened last month when I just treated it like my diary—an open diary this time though. I published immediately, and it felt great.

The pattern was clear: low stakes → daily practice → public sharing → momentum.

With that little bit of experience and my ever-growing enthusiasm for writing (no surprise, I had a whole lot of momentum built at this point) the reasons why it all clicked were:

1. Embraced the process

I’m not a writer, I’m just a person who writes daily—it is a practice. I’m not aiming at anything but surprising myself with what can come out, and I’m totally open when an article takes a different turn (so far, pretty common).

Writing at this point is easier than not writing. I can’t tell the way it’s going, but I’m not constraining the process.

2. I did it for myself

I didn’t seek anyone’s permission or approval to start writing or to start publishing. Even if no one reads it, I will still do it. It’s an internally motivated project, or actually a further development of it.

3. Low stakes, beginner’s mindset

From the very start, I wasn’t pressuring myself to match any standards. The goal has always been to feel good once I’m done with the session. I made it easy for myself, focused on building the habit, and made it non-oppressive and fun. And whenever I was feeling it’s getting boring, I would level up the game—ultimately going public.

4. No overthinking

I just launched myself into it. In many ways, this is my thinking process externalised. Instead of getting ready to write, I would just write and see what comes out. Review, reflect, iterate.

5. Made it public

The only way to let people know what you do is by sharing what you do. I still write for myself and don’t seek to teach or preach. I’m writing here about the things that have helped me grow creatively. And in writing about them, I grow creatively as well.

Why Music Stayed Frozen While Writing Flourished

Music, the very thing I cared about the most, stayed frozen for years because I was obsessed with the finished product or the fantasy of creating a landmark.

Writing flourished because I fell in love with the process of writing. Here, the important part became maintaining the practice and accepting that it can go in an unexpected way.

I also came to conclusion that doing any of this stuff without sharing is kind of pointless. The whole fun is in opening up conversations and allowing something unexpected to happen. Something beautifully unexpected.

Taking the Writing Playbook Back to Music

One day, I asked myself what makes a musician, and my friend Rudy Blu, my former flatmate, came to my mind (hear more from Rudy on EAPX podcast).

Every morning, I’d see him grab the guitar and noodle, and sing quietly to himself in a barely audible fashion. He’d then have one or two evening rehearsals with his band Particls (they just released their debut EP).

They would then have separate time to record their material, but in essence, what I saw was:

morning relaxed practice (for seeding song ideas)

weekly dedicated jams (for songwriting and arranging)

This formula was strangely similar to what I do with writing: daily freestyling, with one session consolidating the spontaneous material into an article ready to share.

What has changed in my approach

I used to play the guitar late in the evening for hours, leaving with a headache, and making no progress. I flipped the script. I give music about 30 minutes daily in the morning before any work when I feel fresh, inspired, and most creative. I note down ideas on my phone, which doesn’t make me feel pressured to play perfectly.

Every Friday morning, I give myself a 2-3h window to record a rough jam to a backing track (finally embracing the context of other instruments).

Given my other commitments in life, this is the amount of time I have availabl,e and I’m making sure I get the most of it without pushing for instant miracles. If it needs 3 years to take shape, so be it.

Because I am already used to connecting with my creative flow early in the morning from all the writing I did, it’s not a matter of inspiration. I always get some ideas. And I allow it to grow at its own pace. I’ll know it’s time to step up the game once it gets boring.

Project learning

What I’ve learned is that you don’t learn a skill and THEN start a project. You start a project and learn the skill along the way. There has to be a clear endpoint and ideally a time frame, or you’re risking never arriving.

By publicly sharing your work, you can protect yourself from the risk of running in circles. In my case, that would mean, for example, missing out on the fact that an article like this one I’m writing needs to conclude in a way that is meaningful and understandable to the readers. So far, this is what I’m having most trouble with—I keep the endings open-ended. Writing to publish made me recognise it.

Equally with my music jams, I couldn’t deny that I simply don’t know how to dialogue with other instruments. I would play something on the guitar, hoping it locks with the drums rather than actually hearing it. So I understood I need to learn how to listen if I want to play.

By sharing your work, you win:

Accountability (by sticking to a schedule)

Feedback (by offering something valuable to others, you can expect some response)

Momentum (by doing more and more of the work, it becomes easier and naturally evolves)

The goal is to eliminate the blurry line between feeling productive and actually progressing. To be real and honest with yourself. This way, you will know where you’re standing, prevent sabotaging yourself by setting unrealistic expectations, and maintain enthusiasm because you will see the progress happening in real time.

I learned HOW to approach music THROUGH writing. Writing was the intermediary experiment that taught me the process. Now I’m taking that process back to the thing I cared about most.

Writing worked for me because it was low-stakes. I didn’t have 20+ years of identity wrapped up in it. It was a side project, something different, fresh. And because it proved to be so effective, now I’m taking that same framework—project learning + public sharing—and applying it to music.

This is why I started publishing my weekly jams to SoundCloud as PXX IGNA (https://soundcloud.com/pxxigna). I call them proto-music, and some of them may become seeds for actual songs. And to my surprise, the results are better than I expected (and I was expecting tragic, so the threshold I set for myself was pretty low anyway).

I now have a way to review and track my progress, test new ideas, and, in the future, use it to find people to play with.

Will it work? I don’t know. But I will undoubtedly find out.

The question to ask is: do you want to spend your life preparing to do the thing you want to do, or actually do the thing?

If you’re feeling stuck like I was, pick a LOW-STAKES creative project, commit to publishing it publicly, and let the feedback loop teach you the process. THEN apply that process to the thing you REALLY want to create. See what happens.